Upton, Dingell Introduce Protecting Married Seniors from Impoverishment Act

It used to be that when one spouse went into a nursing home, the other living at home was doomed to live in poverty. That’s because to qualify for long-term care Medicaid, it meant income and asset limits for the spouse still at home were barely enough to live in. That changed in 1988 when the government changed those asset limits to qualify. But now, with the pandemic and more options for home care, the problem is back. Married seniors are having to choose expensive nursing home care, just so the healthier spouse can keep enough money to live.

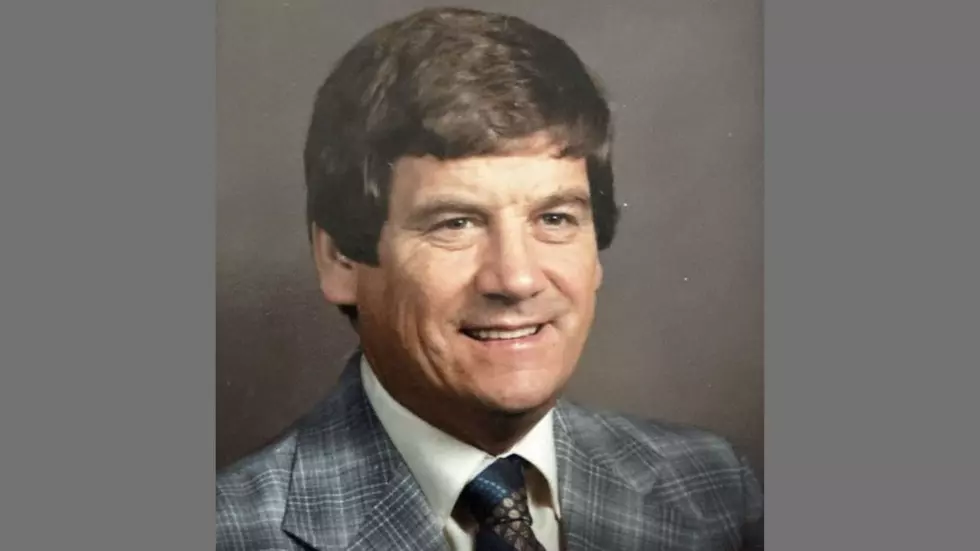

But that problem may change soon, thanks to a bill introduced by U.S. Reps. Fred Upton (R-MI) and Debbie Dingell (D-MI). Today they introduced bipartisan legislation to extend financial protections to seniors who receive long-term care in their home or a community setting. To erase the institutional bias that has led seniors to choose more costly nursing homes over impoverishment, the bipartisan Protecting Married Seniors from Impoverishment Act permanently extends spousal impoverishment protections for Medicaid beneficiaries receiving long-term care in a home or community care setting.

“Our seniors are some of our most vulnerable citizens, and we need to ensure they and their families have the financial protections they deserve to have the quality of life they deserve,” said Upton. “Our bill has strong bipartisan support, and we cannot waste any time trying to move this through Congress. Our seniors are counting on it.”

“A year after this pandemic locked our neighborhoods down, it is abundantly clear that COVID-19 exploited flaws in our broken long-term care system. Seniors, families, and caregivers have been desperate and stressed with nowhere to turn,” said Dingell. “Spousal impoverishment protections are critical in helping families stay together in their homes and communities without going broke. That’s why we must make them permanent.”

Before we tell you what the Protecting Married Seniors from Impoverishment Act includes, just a couple of definitions

Community Spouse. The spouse who is not applying for long-term care Medicaid, also commonly called the non-applicant spouse, healthy spouse, or well spouse.

Institutionalized Spouse. The applicant spouse, sometimes called the nursing home spouse.

Here's what the bill would do:

- A Community Spouse Resource Allowance. While the institutionalized spouse may have no more than $2,000 in savings to qualify for Medicaid in most states, Federal law mandates that states allow the community spouse to retain a modest amount of their assets at the time of application to cover basic living and health expenses. This is called the “community spouse resource allowance (CSRA).” In 2018, the minimum a state may allow a community spouse to retain is $24,720 and the maximum is $123,600. Within those ranges, most states require a split, so for a couple with $100,000 in excess resources, the community spouse may be permitted to keep $50,000.

- Exclusion of a Community Spouse’s Income. Medicaid does not count the community spouse’s income when determining whether the institutionalized spouse is eligible for Medicaid. However, in some states, if the community spouse’s income exceeds a certain threshold, he or she may be liable for court-ordered support for the cost of the sick spouse’s care.

- Minimum Monthly Needs Allowance. The community spouse is also entitled to a minimum monthly maintenance needs allowance (MMMNA). In 2018, this ranges from a minimum of $2,057.50 to $3,090 a month. If the community spouse’s income is below the MMMNA limit, then the institutionalized spouse’s income can be used to supplement the difference.

LOOK: Milestones in women's history from the year you were born

More From WBCKFM

![Lansing Michigan Man Suing Hertz After Wrongful Murder Conviction [VIDEO]](http://townsquare.media/site/87/files/2011/05/98675769.jpg?w=980&q=75)